Bram Stoker’s Dracula was published in 1897. It is a story with many iterations, being the template for the modern vampire narrative. The story is fairly straight forward: Count Dracula requires legal advice to gain access to Britain. The unwitting Jonathon Harker goes to assist the Count in his dealings only to find himself a captive in the mysterious and remote castle. Despite close encounters of the vampiric kind, particularly Dracula’s three sisters, Harker escapes the estate. Dracula follows Harker back to Britain aboard another ship, killing all of the crew on his way. This is where Mina gets involved, who at this time is actually in Budapest where she and Jonathan wed. Dracula begins to search for her but ends up getting involved with a friend of Mina’s, Lucy Westenra. Lucy is in the midst of sorting through marriage proposals from three different men: Dr. John Seward, Quincey Morris, and Arthur Holmwood (or Lord Godalming). When Lucy suddenly begins to wither away these three men band together and collect their resources. Most importantly is a call made to Seward’s old teacher, a Professor Abraham Van Helsing. Helsing immediately identifies the vampiric nature of the illness but does not disclose it to the three suitors. Due to some miscommunication between Helsing and Seward, the Westenra house is left unguarded and is attacked by ‘a wolf’. Mrs. Westenra dies of fright (those sensitive female sensibilities) and Lucy is perceived to be dead soon after. However, after burying Lucy there are reports of children being attacked in the night by a beautiful lady. Helsing returns and, with the assistance of the three suitors, stakes, beheads, and stuffs the mouth of Lucy with garlic (that ought to do it). At this time the newly hitched Harkers return to Britain. Dracula, savvy of Helsing’s plots against him, decides to turn Mina into a vampire. He feeds on her at least three times and also feeds her his own blood, creating a psychic bond (more female subservience). After sweeping London out of all of Dracula’s lairs, the Count returns to his castle in Transylvania. The group hunts him down and, after a spat with some gypsies, they slay the Count. Harker lops of Dracula’s head and Quincey stabs him in the heart, turning the Count to dust. The novel ends with a note from Jonathan Harker, written seven years later, describing that he and Mina remain together with a son.

So, obviously a lot has changed from Stoker’s Mina Harker to Moore’s Mina Murray, and I’m not just talking about the surname. The most prominent change is that Bram Stoker depicts a weak, subservient role for women where Moore turns Mina into a domineering ‘suffragette’.

She’s not only a force to be reckoned with, bravely venturing into opium dens for instance, but she acts as a leader to the League. Part of this role is based in her being original member, the one who collected this rag-tag band of misfits, but also her ability to form plans of action. The only one who doesn’t respect Mina (by the end of the novel) is, of course, Griffin, though, that’s kind of a moot case: Griffin sells out the world. If we were to consider a counter-balance to Griffin’s disrespect it is clearly found in Hyde’s respect, and retribution is fierce.

One of the important features of Mina is how she appears as the ‘English Rose’ archetype. She is pale, thin, petite, mannered even in a chase, and conservatively, yet, femininely dressed. Though it is a rather obvious assertion that the images in a graphic novel are important, physiognomy is also an important aspect in Stoker’s work. As David Glover explains:

“[to Stoker] physiognomy [is] a practical science of social relations, through which personality can be read from the configurations of the human face…. Hence, not only are Count Dracula’s malevolent powers recognizable from his ‘fixed and rather cruel-looking’ mouth or his ‘peculiarly arched nostrils,’ but when we meet Dr. Van Helsing, the man who will orchestrate the vampire’s downfall, moral fitness can be immediately discerned from his ‘large, resolute, mobile mouth’ and his ‘good sized nose … with quick, sensitive nostrils that seem to broaden as the big, bushy eyebrows come down and the mouth tightens'” (987).

This idea of physiognomy as a practical science of social relations applies to Mina quite readily. We expect Mina to be some kind of helpless English girl, something which the near rape in the opium den attempts to prove to us. She also behaves with the staunch manners of a lady, speaking politely though she remains in grave danger. However, the physical scarring of Mina’s neck subverts her ‘English rose’ identity. That ‘otherness’ which she keeps wrapped up allows her to not only take charge of a group of misfits, but it also allows her to survive in dangerous circumstances. Consider her posing as a prostitute. This is not only lewd behavior, unbefitting a true ‘English Rose’, but her survival against Mr. Hyde further subverts that helpless girl that is depicted in Stoker’s Dracula.

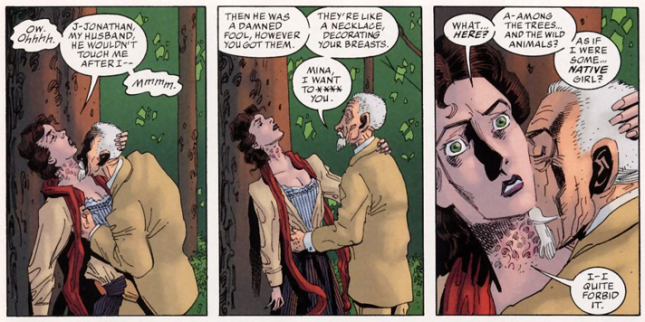

What acts as the ultimate subversion of the ‘English Rose’ is the fetishization of that scarring. When she finally removes that scarf, it is a source of pleasure in the sex act. It is Allan Quatermain, expert on colonizing ‘otherness’, that helps her with this discovery.

I mentioned in my last post that Quatermain becomes a sort of Patriarch to the League. It is this scene in particular that I had in mind as these two fulfill the double taboo of the British colonizer and the British colonized. Though Mina states “I-I quite forbid it,” she cannot resist Quatermain. Rather, as I have already stated, this is part of pleasure of the act, the taboo and fetish relationship. Mina imagines that her scarring makes her “a Native girl.” She is something ‘other’ than British, she is not a member of the nation in this moment. She subordinates her identity to Quartermain as he reinterpolates her as a British subject through his role as a colonizer. In this way her power is given up and she becomes reliant in Quatermain to solidify her British identity.

However, this does not last. She ultimately spurns Quatermain despite his protestations. Moore allows us to trace Mina’s journey from the ‘English Rose’, into minor subversions, into complete inversion, and finally a rejection of that colonized – colonizer interpolation process. Mina’s identity remains open at the close of the novel, which is a true testament to how tricky an author Moore can really be. Furthermore, this rejection of physiognomy as a practical social science reinterprets how identity is founded and read. Moore deflates Stoker’s model of social reasoning.

Works Cited:

Moore, Alan. League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Volume One. La Jolla: America’s Best Comics, 1999.

Moore, Alan. League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Volume Two. La Jolla: America’s Best Comics, 2002.

Glover, David. “Bram Stoker and the Crisis of the Liberal Subject”. New Literary History , Vol. 23, No. 4, Papers from the Commonwealth Center for Literary and Cultural Change (Autumn, 1992), pp. 983-1002.

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/469180